- Home

- Bonnie Leon

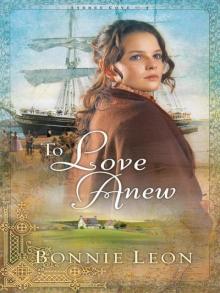

To Love Anew Page 4

To Love Anew Read online

Page 4

Hannah stood on a walkway leading to the front door of an imposing three-story brick home. The Walker estate took up nearly half a block. The house stood close to the street and was squeezed between two other lavish homes. In spite of the crowding there was a small yard with a tiny flower garden. This time of year it held only well-trimmed greenery, but Hannah could imagine what it would look like in the spring.

There were four chimneys reaching from the roof, which reassured Hannah that the home was well heated. Numerous windows looked down on the street, but most had closed draperies, shutting out the light. Curious, thought Hannah. The children must have need of light for their studies.

Hands shaking, she tidied her hair and smoothed her skirt. Taking a deep breath, she tugged on the bell pull. Keeping her spine straight and shoulders back, she stared at the door and waited. The knob turned and the door opened, revealing a small, sturdy-looking woman with silvery hair. Her demeanor was as starched as her apron.

“Yes. What can I do for you?”

Hannah swallowed hard. “My name is Hannah Talbot and I’m here to inquire about the position of upstairs maid.” She couldn’t keep her voice from trembling.“Is the position still available?”

“It is.” The woman studied Hannah. “You’re just a wisp of a thing. Doubt you could do the work.”

“I’m much stronger than I look.”

“Come inside, then. You’re letting in the cold.”

“Thank you,” Hannah said. Thinking the woman didn’t seem the least bit friendly, she stepped inside.

“Wait here,” she said and marched toward the back of the house.

Hannah looked about. She’d been in many fine homes, but never one quite this opulent. An exquisite chandelier hung in the center of the vestibule, showing off the marble floor. The walls were covered with a robin-egg blue brocade paper with floral sprays. And the window draperies were fashioned from heavy, gold fabric—quite elegant. A nymph-like statue sat at the bottom of a sweeping staircase, beckoning one to hurry up the stairs. The house was still and hushed.

Sharp clicking steps echoed from the back of the home. Hannah clasped her hands in front of her.

A slight woman with a pinched expression walked toward her. She was followed by a skinny man with thinning red hair. They both seemed tightly strung.

“I’m Mrs. Walker,” the woman said. “You’ve come to see about the position of scullery maid?”

“I thought you had need of an upstairs maid?”

“Oh yes indeed, but the person we have in mind must do both. Could you manage?” she asked, her voice laced with doubt.

“Certainly.” Hannah kept her elbows tucked in close and kept her hands clasped tightly.

The man studied her, his brown eyes showing intense interest. Hannah guessed him to be Mr. Walker. He sucked on a piece of hard candy that had a strong and distinct odor of mint.

Mrs. Walker moved around Hannah, sizing her up. Hannah felt unnerved and wished she’d never set foot in the house. She didn’t like Mrs. Walker.

“You’re skinny and frail,” the woman said. Before Hannah could defend herself, she continued, “What kind of work have you done before?”

“My mother was a seamstress. I’ve worked with her since I was a girl. I’ve a fine hand with a needle and thread.”

“Your mother’s name?”

“Caroline Talbot.”

“Never heard of her,” she said, her tone dismissive. “And yours?”

“Hannah Talbot.” She pressed her lips together to keep from arguing her mother’s talents. She didn’t dare. She needed this job. “I can get references if you like.”

Mr. Walker leaned against a doorway frame. He seemed to be enjoying the exchange.

“That won’t be necessary.” Mrs. Walker tapped her index finger against her chin and continued to study Hannah from behind dark eyes. “You speak well, girl. Why is that?”

“My mother made sure I was educated. I attended school at the church in my borough.”

Mrs. Walker nodded slightly. “It pays six pence a month, plus your room and board. You may have Sundays off.”

“That would be fine,” Hannah said, careful not to let her relief show.

“When can you start?”

“I have a few things to collect and then I shall return and be ready to work.”

“Fine. I’ll expect you tomorrow, then.” With that, Mrs. Walker turned and strode back down the hallway the way she’d come. Mr. Walker nodded at Hannah, a smile hidden behind his eyes, and then he followed his wife.

Hannah felt breathless. She didn’t know whether to cheer or to cry. She stepped outside, breathing deeply of the cold air. If only she could go to her mum.

4

With his back pressed against a stone wall, John sat on stale hay that had been scattered about the prison floor. After nine days of being locked up, he was weary. For in this place one never truly slept. Despite his fatigue, he felt restless. The first few days he’d paced, but finally gave up the useless walking. It took him nowhere and did little to relieve his agitation.

He looked about the large chamber. At least fifty men in varying degrees of ill health were housed in this single enclosure. It appeared most had been here a relatively long time. Nearly everyone was thin, their skin pallid. And what little clothing they had hung loosely, frayed and threadbare.

One of the inmates walked back and forth in front of the wall opposite John. He’d done that most of every day since John’s arrival. Another sat and stared at a tiny window, as if he’d find salvation there. John had been here a relatively short time and already longed for such simple pleasures as fresh air and sunshine. The rest of the inmates either slept or sat staring at nothing in particular.

He laid his arms over bent knees and rested his cheek on them, longing for sleep and hoping to awaken from this nightmare. A man lying on the floor on the far side of the cell coughed so long and hard John worried he might hack up his lungs. The man had been sick for days. Life in prison was not conducive to good health.

The stink of human sweat and waste assailed his senses. There was no escaping it, and nothing to be done about it. In fact, John could barely tolerate his own stench. He wondered what was to become of him. His attorney had been to visit only once and no one else had come at all. Where was Henry? He was supposed to be his partner. And it was Henry he’d been defending when he got into this mess.

An ache tightened at the base of his throat. And Margaret— why hadn’t she come?

He tried not to think about his upcoming hearing. Each time he did, anxiety set in. Since the fight and his arrest, he’d ceased believing that all things would work out and worried about what else might befall him.

Amidst the moans and groans coming from other inmates, there was a rustling sound within the hay. Lifting his head, he peered through bleary eyes. A large rat scuttled across the floor in front of him. How bold he is, John thought, feeling an unexpected sense of respect for the rodent. Most likely used to the company of men.

John’s thoughts returned to Margaret. He could see her thick auburn hair and lively brown eyes. Why hadn’t she come to see him? He hated the thought of her being exposed to this foul place, yet he longed to gaze upon her wholesome good looks, smell the soapy fragrance of her hair and skin, and hear an encouraging word. Sighing, John leaned his head back against the wall and closed his eyes. Where was she?

Steps reverberated against a stone floor, echoing from a distant corridor. John didn’t bother to look.

The steps stopped and the jailer hollered, “Bradshaw! Ye got a visitor.”

Jolted out of his stupor, John opened his eyes. Could it be Margaret? He looked toward the guard’s station. No. It was Leland Martin, his attorney. As always, he wore an old-fashioned white wig and a three-piece suit with a brocade vest. Leland caught his eye and smiled.

John pushed to his feet. He liked Leland. The man gave little thought to style or to what others might think of him, but he was so

lid and trustworthy. John admired that. Moving stiffly, he made his way to the cell bars.

“How you faring?” Leland asked, his eyes cheerless.

“I’m still breathing. I guess that’s something.” John studied the man. Something in his watery blue eyes told him to prepare for bad news. “So, what have you learned?”

“It’s not good. The man from the pub . . . he died. And his father means to have his revenge.”

John felt as if someone had punched him in the stomach. He took a step back. “His dying . . . what does it mean for me?”

Leland didn’t answer right away. He licked cracked lips and reached through the bars to lay his hand on John’s shoulder. “Have I ever told you how proud your father was of you?”

“At least a hundred times. I appreciate the kindness, but . . . I need to know what I’m to face.”

Leland leveled sad eyes on John. “Most likely . . . the gallows.”

The floor seemed to drop from beneath John’s feet. He grabbed the bars to steady himself. “How can that be? I was simply defending myself in an altercation I’d attempted to prevent. My cousin will tell you. Langdon came after me. It was I who tried to put an end to the fight.”

“You don’t need to convince me. I believe you. It’s the judge we must persuade.” He squeezed John’s shoulder. “All is not lost. You are highly regarded in the community and have no previous record of wrongdoing, so the magistrate may be lenient. I’ll do all I can to attain a lesser sentence for you.”

“What might that be? Is there any possibility of my release?”

Leland shook his head slowly back and forth. “Sorry, lad. You’ve no chance of going free, aside of a miracle. If you escape the gallows, you’ll most likely spend the remainder of your life on one of the hulks or be deported to New South Wales.”

John could barely breathe. He laid his hand against his chest. Trying to get hold of what was happening, he pressed his head against the bars.

“I’m sorry. You don’t deserve this.”

“You’re right there.” John straightened and gripped the bars more tightly. “It was stupid of me to go with Henry. He has a gift for finding trouble and I knew it.” He swiped his hair back. “I’d hoped he’d help sort this out. He’s not thoroughly depraved.”

“He may well be more depraved than you imagine.”

“What do you mean?” John studied Leland, who had been the family’s attorney for a good many years. He could see there was something more that needed saying. “What’s happened?” John asked, not wanting to hear the answer.

Leland stared at the floor, scraping up grime with the edge of his boot. Finally he looked at John, his eyes watering more than usual. “It appears your cousin Henry has departed . . . along with your money and . . . and . . . your wife.”

“No. You’re mistaken. Henry may be irresponsible and even a bit disreputable, but he’d never steal from me, and why would Margaret go with him?” As the question left his lips, he remembered Henry’s womanizing and how often he’d referred to Margaret in a personal way. All of a sudden, John knew why she’d gone, why they’d gone.

His voice flat, Leland said, “I went to the bank to withdraw funds from your account and was told there were no funds. That Mr. Hodgsson had closed the account.” Leland scratched his head at the base of his wig. “I stopped at his home and was told he’d moved.”

“He wouldn’t do that to me. You can’t be right.”

“I then pressed on to your house, hoping to speak with Margaret, but she was gone also, along with her things. I made inquiries and was told that she and Mr. Hodgsson left together. One gentleman, a mister . . . Smith, I believe he said his name was, saw them the morning after you’d been arrested.” Leland stopped and studied the dirtied hay strewn across the floor. “Mr. Smith said he watched while a coachman loaded two trunks. He thought she was going on holiday.”

His doubts piling up like storm clouds, John struggled to grasp the wrong done to him. “Margaret wouldn’t leave me. Not now.”

“Your housemaid concurs with Mr. Smith. It would seem your wife has gone off with that mongrel of a cousin of yours. If I were a younger man and if I should meet up with Mr. Henry Hodgsson, I’d take great pleasure in choking the life out of him.”

John reached through the bars and pressed his hands on Leland’s chest. “There must be another explanation.”

Leland grasped John’s hands. “I wish it were so.” He shook his head. “I offer my regrets.”

Angry heat burned inside John and he withdrew from Leland. How could they do this to him? He dropped his arms to his sides. “All right, then. What is to be done?”

“Henry must be found. And scoundrel though he is, he must be given an opportunity to explain his actions. Litigation may be complicated because he is an equal partner.” He lifted his upper lip sardonically. “Of course he has no rights to your wife. But that you must settle yourself.” He stepped back and glanced at the jailer and then at John. “Before you can deal with him, we must first see that you are released.”

“You said that was impossible.”

“Quite. But one can hope.”

John fought for calm, but he felt as if he’d been set afire. “What are the charges against me?” he managed to ask.

“Murder. But we may be able to get that reduced.”

“To what?”

“Manslaughter.”

“What’s the difference?”

“Murder means you intended to kill Langdon Hayes, and manslaughter says you did it without forethought.” He dusted off his waistcoat. “It could mean the difference between life and death. I’ll do my best to have the charges mitigated.”

John’s mind went back to the day he and Henry had gone to the pub. The thought of his cousin made him want to rage. He shoved the image of Henry aside. There were more important things to think about now.

“There’s a barmaid,” he said. “Her name’s Abbey. She’s a good sort, and she saw everything. She would help.”

“A barmaid? And a woman as well? I’m sorry to say, she’ll be of little use to us.” Leland took out his pocket watch and glanced at it. “I have another engagement. I must go.” He started to leave and then stopped. “Your hearing is two weeks from today. Do your best to look presentable.”

John looked down at his filthy clothing. “And how am I to do that?”

“I’ll bring you something.” He offered a smile. “Don’t lose heart.” Leland walked away and was quickly swallowed by the darkness of the prison corridor.

“Looks like yer goin’ t’ ’ang,” another prisoner taunted. John ignored him even when the man acted as if his neck were being stretched and started making choking sounds. Finally with a loud chuckle, the man walked to the far wall and sat down.

John paid him no mind. His thoughts were on Margaret and Henry and their treachery. How could they have betrayed him so unspeakably?

The creak of wagon wheels carried in from outside, and a crowd that had gathered turned boisterous, shouting accusations and cursing. The death cart, John thought.

No one in the cell spoke. They listened. John didn’t want to hear. He’d seen the sickening sight before—cheers of satisfaction from salivating mobs as prisoners were walked up the scaffolding. They made proclamations of innocence or long confessions of guilt and repentance and then were hanged.

He moved to the far wall and slid to the floor. Pressing his hands over his ears, he tried to shut out the viciousness.

Carrying a candle in one hand and a cup of tea in the other, Hannah moved along the dark corridor behind the kitchen. When she reached the basement door, she set down her tea and opened the door. Hinges, rusted from London dampness, creaked. A cold blast of air swept up from below. She didn’t much like sleeping beneath the house, but it did afford her some privacy. She was the only one with a room in the manor basement.

Stepping carefully, she descended the stairs and followed a short, narrow passageway that led to her room. She

’d left the bedroom door slightly ajar so all she need do was push on it. She closed it using her hip and then crossed to her bedstand and set down the candle and tea.

Hoping for moonlight, she glanced up at a tiny window that sat at street level. There was no illumination. Exhausted and thankful for the end of the day, she fluffed her feather pillow and set it against the wall. Pulling down her quilt, she sat on the bed and lay back against the pillow and then tugged the blanket up over her legs. The room felt like ice. She bent her legs and drew them close to her. Picking up her cup, she sipped the already cooling tea. It was just hot enough to warm her insides a bit. The ritual reminded her of better times with friends and family. She closed her eyes, yearning for those days.

Hannah shivered and looked about the tiny, shadowy room. The darkness felt oppressive. She was allowed only a candle, no lamp. It could be worse, she told herself. I could be on the street.

Stretching out aching legs, Hannah wiggled her toes and tried to think on things she could be thankful for. Instead, she held up her left hand, turned it over, and studied the palm. It was chapped and blistered. She’d only been at the Walkers two weeks, but the days had been grueling. She labored from first light to last. And the children never tired of pestering her.

It seemed nothing Hannah did satisfied Mrs. Walker. Her work was always viewed as insufficient. And the cook was even worse. She seemed a miserable person, forever complaining about something or other. She had no pity for others and in fact went out of her way to make others as miserable as she.

Just that afternoon, she’d made a point of addressing Hannah’s lowly position and what was out of reach for scullery maids. Hannah had been cleaning dishes when late in the afternoon the cook, Mrs. Keller, walked into the scullery. She sniffed. “Ye smell that? It’s fine veal. Whitest meat I’ve seen.” She grinned. “I can nearly taste it—the juiciness of it and oh such a delicate flavor.” Eyes alight with viciousness, she poured hot water into the washing tub.

Wings of Promise

Wings of Promise Touching the Clouds

Touching the Clouds Joy Takes Flight

Joy Takes Flight Enduring Love

Enduring Love The Heart of Thornton Creek

The Heart of Thornton Creek Worthy of Riches

Worthy of Riches For the Love of the Land

For the Love of the Land To Love Anew

To Love Anew Longings of the Heart

Longings of the Heart When the Storm Breaks

When the Storm Breaks