- Home

- Bonnie Leon

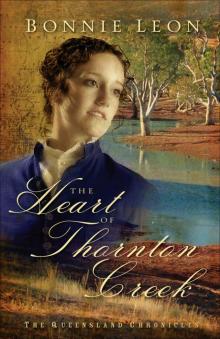

The Heart of Thornton Creek

The Heart of Thornton Creek Read online

© 2005 by Bonnie Leon

Published by Revell

a division of Baker Publishing Group

P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287

www.revellbooks.com

Ebook edition created 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher and copyright owners. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

eISBN 978-1-4412-3939-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Scripture is taken from the King James Version of the Bible.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

About the Author

Acknowledgments

No story is ever written without the help of others. This book is no exception. There are many who gladly shared their insights and knowledge with me.

I met some great blokes not far from home—Richard and Becky Gamble. They own and operate a specialty shop called the Ozstralia Store in Bend, Oregon. It’s wonderful—packed with treasures from the Land Down Under. Richard is an Aussie, born and raised. He and Becky answered my many questions as well as provided videos and books that helped me find my way.

Mark Viney, who not only grew up in Australia but also lived among the aborigines, visited Bend. He spoke to a roomful of Australia enthusiasts and the following day was a special guest at the Ozstralia Store. While he spoke I furiously took notes and did my best to soak in his enthusiasm and knowledge of Australia and its people. I was also privileged to visit with him at the Ozstralia Store, where he graciously answered my questions.

I would be greatly amiss if I were to omit my online Aussie friends. I regularly spent time chatting with some fine people who live in Australia. We had many interesting and fun exchanges while visiting online. They knew me as “the Yank” and graciously included me in their conversations and answered my endless questions. Thanks, mates.

And when I needed to know how to harness horses to a wagon, Steve Bruce came to my rescue. Thank you. If not for you, Rebecca would never have figured out how to harness that wagon.

And finally, I must say thanks to my editor, Lonnie Hull DuPont. You knew my first draft could be better, and your contributions and guidance made it so.

1

Boston, Massachusetts

September 2, 1871

Rebecca Williams knew life had more to offer her than a position of docile wife and mother. However, it seemed that only while on her roan mare’s back did she truly believe it.

Wind snatched at her hat and ballooned the skirt of her riding habit, yet the young Bostonian kept a light hold on the reins and leaned farther over Chavive’s neck. The mare was sure-footed and reliable. Rebecca felt no anxiety, only confidence and pleasure amid the explosive energy and blast of air.

The horse charged past the broad trunk of an oak, then strode toward a wooden fence. Rebecca leaned closer to the mare, gripping the tall pommel at the front of the saddle. When the horse’s feet left the ground, the young woman’s delight intensified and a sensation of power and freedom surged. Rebecca felt a true sense of liberty.

Chavive landed and, without missing a step, moved on, her hooves tearing up damp sod. The prior evening’s rain had left its moist signature, and Rebecca breathed in the rich, heady fragrance of earth and vegetation.

Moving into a grove of maple and heavy underbrush, Rebecca slowed Chavive to a walk. The mare’s sides heaved, and she blasted air from her nostrils. She tossed her head, and the silver bit and headpiece jangled. Rebecca stroked the animal’s neck and spoke quiet words of gratitude.

Rebecca’s thoughts turned to home and the morning’s dispute with her father.

“If my own father won’t engage me, what am I to do about a career?” she’d demanded. “My education is worthless. Absolutely wasted! I don’t understand. I’ve worked beside you for years. I’m well trained, better than most men are when they obtain their first placement. I’m highly qualified. My schooling is completed, and I’m ready to step in and become part of the firm.”

“No man will be interested in a woman with a career!” her father had countered in an uncharacteristically cruel tone.

“I don’t care about a husband. I want more from life than a man and a flock of children.”

Rebecca had meant it. Since girlhood she’d spent countless hours at her father’s office, at first watching him work, then tidying files and such. But in more recent years she’d worked with him, puzzling over cases and discovering creative angles for a defense. She’d treasured the hours laboring alongside him.

There were almost no opportunities for women in the field of law. Still, she could have sought out a position in another firm. There were rare courageous women who had managed to find placements. She wanted to be one of them, but the only prize she truly wanted was to work with her father. Why couldn’t he understand that not all women were meant to be wives and mothers?

She’d been certain he would accept her into the firm. When he’d turned her down, Rebecca had been stunned. It was his nature to give her what she wanted. He’d always been compassionate and overindulgent with his only child.

His closed door had closed all others. Charles Williams was a well-known and respected attorney, and if he wouldn’t engage his own daughter, no other practice would violate his decision.

She rested on Chavive’s neck, stroking her damp coat. Still breathing heavily, the horse glistened with sweat and her nostrils flared with each breath. The ride had been demanding. Rebecca straightened, removed her hat pin, repositioned her felt hat, and attached it more securely. I must be a sight, she thought, brushing damp strands of dark hair off her forehead and smoothing the tendrils clinging to her neck back into place.

Patting Chavive, she thought, I know my father thinks I’m intelligent. I was top of my class. And how many times has he told me that it was only my sharp mind that saved a case? She smoothed her gloves. It’s time I had a career. I don’t fit in Boston society. I must make Father understand.

Rebecca studied the broad valley dotted with farms. Her eyes wandered to Massachusetts Bay with its waters glinting like finely cut gems. This place usually soothed her, but she felt only a scrap of peace. Today even with God’s creation laid out before her, she couldn’t rid herself of the sense of strangulation pressed upon her by society.

I don’t understand, Lord. You know my heart, and your holy Word says you will give us the desires of our hearts. You created me as I am. Why, then, would you restrain me from fulfilling my passion?

Chavive stomped a foot and tossed her head. Rebecca pulled up on the reins. “All right. We’re off.” She nudged the mare forward and turned her t

oward home. I’ll talk to Father again. I’m sure I can make him understand. He’s always been a fair man.

Their need for a good run satiated, horse and rider leisurely followed a trail through the forest and into an open field splashed with color. More than once Rebecca was tempted to stop and pick from summer’s last offerings. There were blue lobelia, scarlet trumpet creepers, dainty bluebells, and other flowers she couldn’t name. But she didn’t dally. The closer she came to home, the more urgently she felt the need to speak with her father. Passing through the final gate, which led to a broad pasture beside her home, she caught the heavy, sweet fragrance of honeysuckle. Rooted along the fence, the plant embraced the weather-battered planks.

The sprawling, three-story house peeked out from behind trees and shrubbery. Rebecca pulled on the reins and stopped to study her home. An expansive, well-trimmed lawn dappled by gardens bursting with color surrounded the house. Brick steps led to a covered front entrance framed by broad pillars supporting a second-story balcony. White-trimmed windows gazed out on the serene surroundings.

The home had always felt like a sanctuary to Rebecca, and the sight of it provided an inner quiet. She’d had many good days here.

Her eyes rested on a window on the second floor. Someone stood there, gazing out. It must be her aunt Mildred watching for her. Rebecca smiled. Mildred was always watching, always concerned. A spinster, she’d filled the role of mother since Rebecca’s mother, Audrey, had died of pneumonia. Rebecca had been only five years old.

Though she’d been young at the time, she had memories of her mother’s warm smile and her energy. Rebecca’s father had always said she was the spitting image of her mother not only in her looks but in her feisty spirit as well. Rebecca liked that—she remembered the vibrant brown eyes that had said, “I love you.” She sighed. Her mother’s absence was a grave loss.

Rebecca gently tapped Chavive’s hindquarters with her riding crop and cantered across the field and to the stables. Jimmy, the stable hand, greeted her with his usual open smile.

“Did you have a good ride?” he asked, taking hold of the halter.

“We certainly did.” Rebecca lifted her right leg over the sidesaddle horn and attempted to slide from the horse. However, instead of making a graceful dismount, she fell forward when her dress caught on the saddle horn, and she nearly toppled on the boy as he attempted to break her fall.

“Dash it all!” Rebecca sputtered. As she pushed herself upright, her eyes met Jimmy’s. “Er . . . I mean, land sakes.” Rebecca detested profanity, but on certain occasions she forgot her own mouth.

“Give it no mind, miss. I’ve heard lots worse. Even from my own father.” He grinned.

“Well, I’m sorry for my irritation.” She yanked the last of her cumbersome black skirt free and smoothed it over her hips. “Dungarees would be so much more practical.”

“Trousers, ma’am?”

“Yes.” Rebecca straightened her hat. “And don’t call me ma’am. We’ve known each other too long for that.”

“Well, my father told me . . .”

“I know. I’ll talk to him.” Rebecca glanced about. “In fact, I’m going into town. Could you find him and tell him I’ll need the surrey?”

“Yes, ma’am . . . Rebecca.” He took Chavive’s reins. “And then I’ll cool your horse down and give her a good brushing.”

“Thank you,” Rebecca said and briskly walked to the house, stopping only to pluck a yellow rose from the garden. Mildred stepped onto the front porch just as Rebecca took the steps. “For you,” Rebecca said, holding out the rose.

“Why, thank you.” Mildred took the flower and smelled it. “Mmm. There’s no finer fragrance, don’t you agree?”

“I do, absolutely. I think we should plant more.” Stepping indoors, Rebecca sniffed the air. “Smells wonderful. Fresh bread and one of your amazing stews?”

“Yes.” Mildred smiled, and her narrow face rounded slightly. Her heels clicking on the vestibule tiles, she marched toward the dining room, where her steps were quieted by an elegant woven rug. “Did you have a nice ride?”

“Yes. Lovely. I never tire of riding, especially not Chavive. She seems to know my mind.”

“It was rather chilly this morning.”

“Fall isn’t far away.” Rebecca followed Mildred into the kitchen. “So did you give the cook the day off again?”

Mildred dusted flour from a cabinet. “You know I don’t need her.”

“Yes, you do. You work too hard.” Rebecca took a small hand-painted vase from a cupboard and filled it with water. She took the flower from Mildred and plunked it in the vase. “You’re a wonderful cook, but there’s no harm in having someone to help.” She set the vase on a small mahogany table in a kitchen alcove. “I’m going into town to see Father. Is there anything you need me to get for you?”

“No.” Mildred pursed her lips. “You’re not going to continue this morning’s dispute are you?” She pressed the palms of her hands together. “I do hate it when you two quarrel.”

“We weren’t quarreling. But we didn’t finish our . . . discussion. I’m not certain he really understands my point of view. However, I’m convinced that once he realizes how important all this is to me, he’ll come to a more reasonable conclusion.” Rebecca hurried toward the stairway. “I’ll just change and be on my way.”

“All right, then,” Mildred said with a sigh. “Dinner will be ready at six o’clock sharp. Don’t be late.”

“I promise,” Rebecca said. Then, deciding her aunt needed reassurance, she turned, retraced her steps, and planted a kiss on Mildred’s cheek. “I’d never miss one of your superb meals,” she said with a smile, then hurried upstairs.

Rebecca’s mind clipped along at a much swifter pace than the steady clomping of the horses’ hooves against brick. As if preparing a case, she thought over just what to say and decided forthrightness was best, no waffling. She considered demanding that her father show her the respect due someone who had given so much time to his business and who had worked so hard to reach a noteworthy goal. She would certainly remind him that if she weren’t his daughter he would surely give her consideration. He’d always been clear about providing everyone a fair hearing.

Confident she would have her way, Rebecca gazed at the buildings of Boston’s business district. She liked the tidy look, the brick construction and rows of framed windows, but it was the lively activity of industrious businessmen and careful consumers that she enjoyed the most. It was stimulating, nearly as much so as riding Chavive.

Amid important business ventures, men sporting smart-looking suits and puffing on cigars stood and talked about shipping ventures or politics. Women wearing the latest fashions, which always included their finest hats, strolled along the sidewalks, stopping occasionally to consider a window display or to chat.

Rebecca loved the city and hoped to one day live in a modern downtown apartment. That way she’d be in the center of activity. Of course, it would mean she’d either have to move Chavive to a stable nearby or travel out of town to ride. Neither idea appealed to her. Her mind wandered back to the woods and open fields surrounding her home, then to the house itself. She would miss it awfully. Maybe visiting and working in the business district would be enough.

“Good day.” A woman’s trill cut into Rebecca’s musings.

She focused on the origin of the voice. Mrs. Hewitt waved and smiled, bobbing her head, crowned by a black velvet bonnet trimmed in soft faille. It had pink roses in front and a white ostrich plume scooping down in back. Rebecca preferred simpler, more practical bonnets.

“Good morning,” Rebecca said. “How nice to see you. Is your family well?”

“Yes, very. Yours?”

“We’re all fine.”

Inwardly, Rebecca sighed at the superficial exchange. It was always the same. Mrs. Hewitt was a kindly enough person, but nothing in her life was remotely interesting to Rebecca.

“Wonderful to see you,” Mrs. Hewitt

chimed. “Have a lovely day.”

Rebecca nodded. A sudden breeze caught at her bonnet, and she firmly held it down. Open carriages were immensely more comfortable in warm weather, but they did have their drawbacks.

Mrs. Hewitt bustled away, looking as if she’d been cinched up so tightly she might pop. Rebecca didn’t believe in allowing her stays to be tight; the constriction was uncomfortable, and her slim figure didn’t require it. She’d have been just as happy to forgo her corset altogether. However, Aunt Mildred would never allow it. Rebecca smiled at the thought, deciding that one day she would escape the house, unlaced and free.

The carriage stopped, and Tom Barnett, the coachman, climbed down and opened the door for her. She stepped onto the sidewalk.

“I shouldn’t be long,” Rebecca said before briskly taking the steps at the front of her father’s office.

She sauntered down a dimly lit corridor and stopped at the door leading to his suite. After smoothing her skirt and tucking in a loose strand of hair, she swept into the room.

Rebecca removed one glove and waved it at a plump woman sitting behind a flat-topped desk cluttered with papers and files. “Hello, Miss Kinney. I’m here to see my father.”

Stripping off the other glove, she strode across the room to the door leading into her father’s office. Before Justine Kinney could speak, Rebecca breezed through the door.

“I have . . .” She stopped. Her father scowled at her. A good-looking, young man sat in the chair in front of his desk. “Oh, I’m sorry, I—”

“I’m busy at the moment,” Charles Williams said, standing and still wearing a frown. “Could you—”

“No. Please.” The young man stood, swiping back a thatch of blond hair. “Quite all right, ’ere. We’ve accomplished a fair bit already, eh, Mr. Williams? We’ve been working hard. How ’bout we give it a go again tomorrow?”

“I’d be more than happy to finish up here.”

“Seems fair I give you some time with the . . . missus?”

Charles grinned. “No, no. She’s not my wife. She’s my daughter.” He moved out from behind the heavy oak desk. “Daniel, may I introduce my daughter, Rebecca. Rebecca, Daniel Thornton—a client.”

Wings of Promise

Wings of Promise Touching the Clouds

Touching the Clouds Joy Takes Flight

Joy Takes Flight Enduring Love

Enduring Love The Heart of Thornton Creek

The Heart of Thornton Creek Worthy of Riches

Worthy of Riches For the Love of the Land

For the Love of the Land To Love Anew

To Love Anew Longings of the Heart

Longings of the Heart When the Storm Breaks

When the Storm Breaks