- Home

- Bonnie Leon

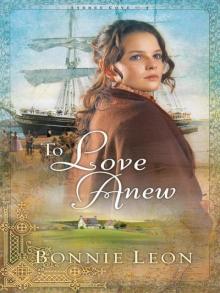

To Love Anew

To Love Anew Read online

To Love

Anew

Other books by Bonnie Leon

The Queensland Chronicles

The Heart of Thornton Creek

For the Love of the Land

When the Storm Breaks

SYDNEY COVE, BOOK I

To Love

Anew

BONNIE LEON

© 2007 by Bonnie Leon

Published by Fleming H. Revell

a division of Baker Publishing Group

P.O. Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287

www.revellbooks.com

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Leon, Bonnie.

To love anew / Bonnie Leon.

p. cm. — (Sydney Cove ; bk. 1)

ISBN 10: 0-8007-3176-X (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-8007-3176-2 (pbk.)

1. British—Australia—Fiction. 2. Young women—Fiction. 3. Australia—

Fiction. I. Title.

PS3562.E533T6 2007

813 .54—dc22

2007010820

Scripture is paraphrased from the New King James Version. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Contents

Acknowledgments

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Jayne Collins, an Australian who lives in Queensland and has been my research partner. She’s a teacher, a historian, and a woman who is passionate about her country. Because of her sacrifice of time and her dedication to this project, I am able to present this story with confidence. Thank you, Jayne, for your assistance and your encouragement.

1

Hannah Talbot stared at the freshly covered grave. The ache in the hollow of her throat intensified and tears seeped from her eyes. “Mum,” she whispered, and then her words choked off. She tried to swallow away the hurt.

Wiping her tears, she closed her eyes. How was this possible? It seemed only days ago that she and her mother had been laying out a pattern for a woman’s gown. It was lovely, made of pink-and-white-striped taffeta. Her mother had chatted about how fetching the young woman would look at her debut.

Reality swept through Hannah, agony swelling with its truth. She’s gone! Her legs felt as if they might buckle. “How, Lord? How can it be?”

Her eyes roamed over the churchyard. There were many headstones—so many loved ones gone. Each time she came to visit she noticed other gravesites. Today she’d stopped at a cluster of headstones, all belonging to one family. They’d been taken within weeks of each other.

Some graves had only crosses. Hannah thought it sad that a person’s final resting place didn’t display their name. Fortunately, she’d managed to procure enough funds for a simple casket and headstone.

A chill wind swept across the frozen ground and shivered through the limbs of bare trees. “Why, Lord? Why my mum?”

The day her mother had come down with fever, the late winter sun had slanted through the windows of their tiny home. They’d worked in the sewing shop at the front of the cottage. During a respite, they’d sipped tea and talked of the coming spring and how much fun it would be to picnic in the countryside beyond the London streets.

A sharp draft of air caught at wisps of brown hair and tossed them into Hannah’s eyes. Brushing them aside, she pulled up the collar of her coat and closed it more tightly around her neck. “I miss you, Mum,” she said, as if her mother might hear. “I don’t know how to live without you.” She took in a tattered breath.

Kneeling, Hannah pulled her hand out of her pocket and rested it on the frozen mound. She could feel the coldness of the ground through her glove. Outside the gate, a carriage rambled past, its inhabitants tucked safely inside. Hannah watched as it rolled down the street and moved on around the corner. Once more, her world turned quiet. She was alone.

Hannah stood. The churchyard suddenly felt menacing. She tried to concentrate on warm memories—hours at her mother’s side learning the intricate stitches needed to create fine garments, listening to stories of her mother’s youth and of her father and grandparents. Her mother often spoke of God—his statutes and his love.

She stuck her gloved hands back inside her pockets. “I shan’t come back,” she said. “You’re not here. There’s nothing of you here.” She took a deep breath and smiled softly. “You’re in our Father’s presence, just as you always said you would be one day. I want to be happy for you. And I am, really . . . happy for you and for Papa. It’s me I’m crying for. Forgive my tears. I know you wouldn’t want them.” She sniffled into a handkerchief.

It was time to open the shop. Hannah knew she must go. Yet, she lingered and stared at the frozen pile of earth. What if this was all just a terrible dream? If only it were. Or perhaps her mother could return. Jesus’s friend Lazarus had. She closed her eyes. Lord, would it be too awfully selfish of me to wish her back? I miss her so.

Hannah remembered her mother’s last days. She’d lain abed for weeks, shivering with fever and then clammy with sweat. Bit by bit she’d faded, and then one morning she was gone. It would be selfish to drag her back from the Father’s arms and the glory of heaven. Hannah hugged herself about the waist. “No. I won’t ask,” she said. “I love you too much for that.”

Her hands shaking with cold, Hannah pushed a key into the lock and turned it. The door fell open just a bit and a bell chimed softly. Hannah smiled. She loved the little bell hanging from the doorknob. It had been her idea. She was no more than seven when she’d seen one just like it at the millinery shop. Hannah remembered how fast her feet had carried her home. “Oh, Mum,” she’d cried. “Mr. Whittier has the finest bell at his store. It hangs from the door. And when the door opens it makes a lovely sound. Could we get one? Please?”

Her mother had explained that it was an unnecessary expense, and Hannah had tried to put it from her mind. A few days later, the first customer of the day arrived and Hannah heard a soft tinkle when the door opened. Jumping up and down and clapping her hands, she hugged her mother and then opened and closed the door at least a dozen times, just to hear the gentle ringing. She thought it sounded even better than the one at the millinery shop.

Pushing the door shut and closing out the cold, Hannah felt the familiar whisper of Jasper, her old tabby cat, as he rubbed against her skirt. She picked him up and held him close, pressing her face against his long fur. He felt warm and his purr vibrated contentedly. “Good morning. Did you find any mice to eat? I hope so, I’m afraid the larder is nearly bare. Perhaps there’s a bit of milk yet.”

She lifted a pitcher of milk from a shelf on the back porch, then broke a thin layer of ice on top with a wooden spoon and poured some into a tin. “There you go,” she said, setting the bowl on the floor. Jasper eagerly lapped it up.

“Now, for some warmth,” Hannah told him, and moved toward the coal stove. Opening it, she peered inside. There were a few hot coals left. After dropping in a handful of straw, she scooped co

al out of the hod and placed it on the fledgling fire. Closing the door, she set the hand shovel back in the coal scuttle and then stood beside the stove, hoping to warm her body. If only she could afford to build a large, hot fire. That would feel so much better, but there was little coal left and her money was gone. Fear flickered to life, but she forced it from her mind. It would do no good to think on the things she could not change. The Lord would provide, somehow.

Moving to the tiny kitchen behind the shop, she took the last of a loaf of stale bread and carved a thin slice. Next, she spooned cheese from a ball and spread it on the wedge. She folded the crust around it and took a bite. The mix of strong and mild flavors tasted rich, and the emptiness in her stomach felt better. She sat in a wooden rocker and Jasper jumped into her lap. Stroking his soft fur, she fed him a bit of the cheese and bread, and he settled, chewing contentedly.

The bell jangled and Ruby Johnston stepped in. Her open, friendly face fractured into hundreds of tiny lines when she smiled. “Good mornin’, dear. How ye faring?”

Ruby’s presence warmed the inside of the shop and Hannah’s heart. She adored the robust, square-built woman. As far back as Hannah could remember, Ruby had been part of her life. And since her mother’s death, the kind woman had spent many hours at Hannah’s side. “Oh, you know, I’m managing. Went to Mum’s grave this morning.”

Ruby raised an eyebrow. “So early? Ye spend a lot of time there. Ye think it wise?”

“Probably not. I just want to be close to her.”

Ruby sat on a straight-backed chair. “She’s not there, ye know.”

“Yes. I do know.” Hannah scratched the underside of Jasper’s neck, burying her fingers in his thick coat. “I’ve been considering not returning.”

“Just as well, I’d say. Too cold these days. And it’s not seemly for a young lady to be wanderin’ ’bout a graveyard. I don’t think yer mum would want that.”

“You’re probably right. Every time I go I feel lonelier. I miss her so.” Hannah swallowed the last bite of bread. It ached all the way down. Shaking her head, she said, “How can she be gone? She deserved to live.”

“That she did, dear. But one can’t know the ways of the Lord. We just have to trust him.”

“Truly. And I’m trying. But life seems pointless without her, and I don’t know how I’ll keep the shop open. I’ve already had patrons withdraw orders.”

Hannah could see apprehension in Ruby’s brown eyes, and creases lined the older woman’s forehead. “It’s a shame. Yer a fine seamstress.” Ruby smiled. “But it’s not the end of the world. There’ll be new orders, I’m sure.”

“I hope you’re right. I’m not the seamstress my mother was.”

“No. That yer not, but ye do have a fine hand all the same.”

The bell jangled as the door opened. Keeping her chin high and her shoulders back, Ada Templeton stepped inside. She had a way of looking down at people, even those who stood taller than she, which weren’t many for she carried quite a lot of height for a woman. Leaning on a cane, she moved into the room, peering suspiciously at Ruby. Her eyes went to Hannah. “Child, it’s chilly in here. You need to add more coal to your fire.”

“Yes. I quite agree,” said Hannah, thinking that she would love to add more if only she could. She pushed out of her chair, dropping Jasper onto the floor. He raised his back and tail and strolled toward the kitchen.

“I’ve not been able to finish your gown, Mrs. Templeton. With my mother’s death and all the arrangements, I . . .”

“Your mother has been gone two weeks or more. Isn’t that right?”

“Yes.”

“I’d say you’ve had more than ample time to get your life in order, including your work.” She tugged at a glove. “No matter. I expected this.” She bobbed her head and a bow on her showy lace hat tottered. “Your mother was very capable. I can’t expect you to be as skilled or as clever with designs as she. I’ve found a fine seamstress who said she’ll be able to fulfill my needs and will also complete any unfinished work.”

Hannah was flabbergasted. “I know I’m not as accomplished as my mother, but I’m quite capable. I can have the dress done for you promptly.”

“I can’t wait.” Ada turned toward the door. “Please deliver the dress to—”

“She’ll not deliver anything for the likes of ye,” Ruby stormed, moving toward the woman.

Ada gasped and backed away.

“If ye want yer gown, ye’ll be takin’ it with ye and ye’ll take it now.” Ruby moved past Ada and hustled to the back of the shop where gowns in varying stages hung. “Which one is it?” she snapped, grabbing one gown after another. She swung around and looked at Ada. “Which one?” she demanded, bristling like an angry mother hen.

“Why, the purple—”

Before Ada Templeton could finish her sentence, Ruby grabbed the gown off its hanger, flung it over her arm, and strode toward the woman. “Here ye go, then. Take yer dress and be off with ye. We’ve no need of business like yers.”

“Well! I never!” Ada Templeton clutched the dress to her chest. She turned to Hannah. “You’ll not stay in business long with this kind of behavior! I don’t feel the least bit sorry for you, young lady. You’ve brought this on yourself.” With that, she stormed out of the shop.

Hannah stared at Ruby. She didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. She loved Ruby, but her dear friend had a fondness for giving in to her emotions. “Ruby, I needed that sale. I could have handled her.”

“Ye wouldn’t have, luv. She already had her mind made up.” Ruby dropped into a chair. “I am sorry, though, for raising such a fuss. Maybe I did muck it up. I truly am sorry. It’s just that I can’t abide those hoity-toity ladies. She had no right to treat ye badly.”

“I know you meant well, Ruby.” Hannah moved to the stove and lifted a kettle. “Would you like a cup of tea?”

“I would at that. I’m all out at my house.”

Hannah poured two cups of the weak tea. After serving Ruby, she returned to her rocker. “I wish I had a sweet to offer.”

“Not to worry. These days, none of us have money enough for pleasures.”

Hannah stared into the pale golden drink. She wanted to cry, to let her tears spill freely and never stop. But then, she’d spent so many tears already, she wondered if she had any left. She looked at Ruby. “I don’t know what I’m going to do. The rent is owing, and Ada Templeton isn’t the first to withdraw an order.”

Ruby nodded her head in sympathy. “It’s not fair, none of it.”

“Mum often said, ‘Life isn’t supposed to be fair, but it can be good.’ I try to be thankful for the small things.” She took a sip of tea. “I need her so badly. She’s the one who kept me steady—always reminding me of God’s love and compassion. She believed he watched over and cared for all his children all the time.”

Hannah set her cup in its saucer. “I’m confused, Ruby. If he is such a merciful, caring God, why would he take my mother? She never asked for much, except to be able to work and to keep food on the table and a roof over our heads. I never heard her speak an unkind word.”

“Caroline was the closest thing to a saint I’ve ever known.” Ruby smiled. “She was a good friend to me and my family.” Her eyes glistened.

“Of course, you miss her too. Here I’ve been complaining about my loss and I’ve forgotten how much you’ve lost.”

“Oh no. Not to worry ’bout me. Friends aren’t the same as family. I know that. I remember my own mum’s passing. I’ve not stopped missing her.”

Quiet settled over the room as each woman’s thoughts stayed with their loved ones. Hannah set her cup and saucer on a small table and walked to the tiny window at the front of the shop. She gazed outside at falling crystalline flakes. “Snow has started. I hope it doesn’t get too bad.”

“I’ll be glad to see spring.”

Hannah turned and looked at her friend. “What am I to do? There isn’t enough money for rent, and not

only have I lost work, I’ve not had any new orders.”

“I wish I could take you in, luv. You know I would if I could. But with my daughter and her little ones and that brute of a husband . . .” She looked away and shook her head.

“Please don’t feel badly. I don’t expect to be taken in. I want to care for myself.” Hannah brushed a wisp of hair off her face. “I doubt I’ll ever marry. I need to find a way to be independent.”

“You’re a lovely girl,” Ruby said. “You’ll find a man.”

“I’m already past twenty-one. And I’ve had no proper suitors. I dare say, I’m not so fine-looking.”

“You’re quite comely. You’ve lovely hair and your brown eyes dance with light, child. The right one has just not come along yet. And it’s possible you’re just a bit too particular. I remember that one young man—the carpenter—he was quite taken with you.”

“That may be, but he was more taken with himself. I just couldn’t abide that.”

“Well, what about the smithy? He’s a fine gent.”

“Oh yes. But he has one flaw—too great a love for the spirits.”

“Someone will come along, and he’ll be just the one.” Ruby smiled and stood. “I heard of a gentleman named Charlton Walker. He’s a magistrate, I believe—a fine gentleman.”

“A magistrate? What are you thinking? He’d never be interested in someone like me.”

“No. No, deary. You didn’t let me finish. He’s in need of an upstairs maid. Might tide ye over for a bit. He has a wife and children who’ll need some mending done from time to time too, I might think.”

“Yes. I suppose.” The idea of being a housemaid raised no enthusiasm in Hannah. She didn’t want to work for someone else. She was a seamstress. She loved the way a piece of cloth came to life when it was matched with the right pattern and then clothed a fine figure. Even simple fabric could become something special. “I’ll think on it.”

“That’s fine, dear. Well, I’d best get myself home. My children and my husband are certain to be hungry.” She rested her hands on Hannah’s shoulders and kissed her cheek. “Let me know what I can do, eh?”

Wings of Promise

Wings of Promise Touching the Clouds

Touching the Clouds Joy Takes Flight

Joy Takes Flight Enduring Love

Enduring Love The Heart of Thornton Creek

The Heart of Thornton Creek Worthy of Riches

Worthy of Riches For the Love of the Land

For the Love of the Land To Love Anew

To Love Anew Longings of the Heart

Longings of the Heart When the Storm Breaks

When the Storm Breaks